Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York is a towering achievement in screenwriting, renowned for its labyrinthine structure, existential depth, and meta-narrative brilliance. A film about a theater director’s attempt to create an ever-expanding, hyperrealistic stage production, it captures the complexity of human life and the artistic process. Writing complex narratives like Synecdoche, New York involves balancing ambition with coherence, emotional resonance with intellectual challenge. This article dissects Kaufman’s methods to uncover lessons for screenwriters aspiring to tackle intricate storytelling.

Breaking Conventional Narrative Structures

A Theater of Infinite Layers

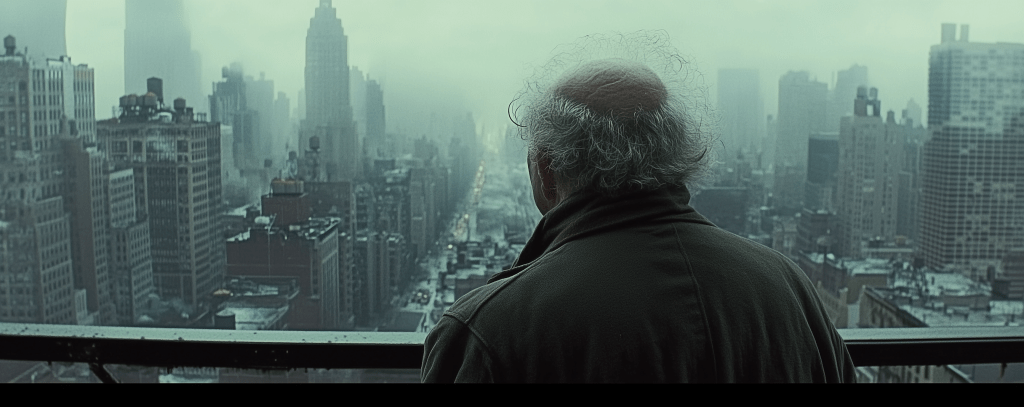

At its heart, Synecdoche, New York revolves around Caden Cotard, a theater director whose life and art blur together. As he builds a life-size replica of New York City inside a warehouse for his play, the line between the play and reality dissolves. Kaufman’s script mirrors this complexity, eschewing linear storytelling for a recursive, self-referential narrative.

This technique serves to immerse the audience in Caden’s existential crisis. His ever-expanding project becomes a metaphor for life’s unrelenting complexity and the human need to find meaning. Kaufman’s willingness to abandon conventional three-act structures for a fractal-like approach invites screenwriters to explore how narrative forms can reflect thematic content.

Example for Writers: To write a similar narrative, consider how the structure of your story can mirror its themes. If your story is about chaos, for instance, a fragmented narrative might better reflect that than a traditional plot.

Themes of Mortality and Meaning

Life as Art, Art as Life

Synecdoche, New York delves into profound themes: mortality, legacy, and the nature of art. Caden’s obsessive creation becomes a way to confront his mortality, but as the project spirals out of control, it highlights the futility of fully understanding or encapsulating life. Kaufman’s script repeatedly reminds the audience of time’s relentless march through visual and narrative cues, such as characters aging abruptly or dialogue referencing death.

For writers, this underscores the importance of grounding abstract themes in relatable human experiences. Kaufman’s exploration of mortality resonates because it is filtered through Caden’s personal struggles—his failing health, crumbling relationships, and obsessive need for artistic perfection.

Writing Tip: Anchor your thematic exploration in character-driven moments. A universal theme like mortality gains power when it’s revealed through specific, personal stakes.

Meta-Narratives and Self-Reflection

Stories Within Stories

Kaufman layers his screenplay with meta-narratives, where characters play other characters, creating an infinite regression of stories. In the warehouse, actors play real-life counterparts, who themselves are acting out their own lives. This recursive storytelling mirrors the human tendency to interpret life as a narrative—a story we tell ourselves to make sense of chaos.

The meta-narrative also invites audiences to question their role as observers. Are they watching Caden’s life, his play, or Kaufman’s commentary on storytelling itself? This multi-layered approach enriches the narrative, making it as much about the act of creation as it is about the story being told.

Lesson for Screenwriters: Use meta-narratives to explore storytelling itself, but ensure they serve a purpose. Self-referential layers should illuminate the central themes, not distract from them.

The Role of Surrealism in Complex Narratives

Blurring the Lines of Reality

Kaufman incorporates surrealist elements to heighten the emotional and philosophical stakes. Houses burn indefinitely, time shifts unpredictably, and characters’ roles blur. These surreal touches make the narrative dreamlike, reflecting Caden’s deteriorating grasp on reality and reinforcing the film’s existential themes.

Surrealism, when used effectively, allows writers to explore abstract ideas in ways that realism might constrain. However, it requires careful calibration; surreal elements must feel integral rather than arbitrary.

Practical Insight: Introduce surreal elements that echo the emotional or thematic underpinnings of your story. For example, a character’s fragmented memory might be mirrored by a fractured narrative timeline.

Character Complexity and Emotional Resonance

Flawed Protagonists

Caden Cotard is not an immediately likable character. He is self-absorbed, indecisive, and often lost in his own head. Yet, his flaws make him deeply human, allowing audiences to empathize with his fears and desires. The supporting characters—each representing aspects of Caden’s psyche or life—add depth, serving as mirrors to his internal conflicts.

Kaufman crafts characters that feel simultaneously exaggerated and painfully real. Their interactions provide moments of levity, heartbreak, and profound insight, grounding the film’s more abstract ambitions in human emotion.

Screenwriting Takeaway: Embrace flawed, multi-dimensional characters. Their struggles, contradictions, and vulnerabilities will resonate with audiences far more than perfect heroes.

Dialogue as a Tool for Philosophical Inquiry

Existential Conversations

The dialogue in Synecdoche, New York is dense, often serving as a vehicle for existential inquiry. Characters discuss death, purpose, and identity in ways that feel both profound and conversational. Kaufman strikes a balance between philosophical depth and emotional accessibility, ensuring that the dialogue enhances rather than overwhelms the narrative.

Example for Writers: Use dialogue to reveal your characters’ internal struggles while advancing the story. Philosophical conversations can be compelling when they feel organic to the characters and their situation.

Visual Storytelling in Complex Narratives

The Power of Symbolism

Kaufman’s screenplay is brought to life through rich visual symbolism. The warehouse becomes a microcosm of Caden’s mind, and the decaying set pieces mirror his failing health and waning grasp on reality. Kaufman uses these visuals to externalize the internal, allowing audiences to “see” Caden’s thoughts and emotions.

Tip for Writers: Collaborate with directors and visual artists to translate abstract themes into tangible imagery. Consider how settings, props, and visual motifs can deepen your story’s impact.

Lessons from Synecdoche, New York for Aspiring Screenwriters

Writing a complex narrative like Synecdoche, New York requires a bold vision, meticulous planning, and a willingness to experiment. Here are some practical takeaways for screenwriters:

- Start with Themes: Anchor your narrative in a central theme or question, and let the story’s structure and characters emerge from it.

- Embrace Non-Linearity: Experiment with narrative forms that reflect the story’s emotional or philosophical dimensions.

- Balance Surrealism with Humanity: Use surreal elements to amplify your themes but ensure they remain emotionally grounded.

- Layer Your Story: Incorporate meta-narratives or subplots that enrich rather than confuse the central narrative.

- Prioritize Emotional Resonance: Even the most abstract story needs relatable characters and stakes.

Conclusion

Synecdoche, New York is a masterclass in writing complex narratives that challenge and captivate. Kaufman’s ability to weave existential themes, meta-narratives, and surrealism into an emotionally resonant story is a testament to the power of ambitious storytelling. For screenwriters, it’s an inspiring example of how to push the boundaries of narrative form while remaining deeply human at its core. Whether you’re crafting a straightforward drama or an intricate puzzle of a story, the lessons from Synecdoche, New York remind us that complexity, when handled with care, can lead to profound cinematic experiences.

✍️ Whether you’re mastering the art of dialogue, structure, or character development, the power of AI can be a game-changer in your writing journey. My Free Ebook, ‘AI for Authors’ delves into how AI-powered prompts can provide a unique edge to your storytelling process. If you’re intrigued by the prospect of supercharging your fiction skills, download your free copy today and explore new horizons in creative writing.