Few films demonstrate how powerful perspective can be in storytelling as effectively as Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954). A masterclass in crafting suspense, the film employs a limited point of view—both literal and narrative—to immerse the audience in the protagonist’s paranoia and isolation. By placing the viewer squarely in the shoes of its central character, Hitchcock draws out tension, fuels uncertainty, and keeps us questioning what we think we see.

For screenwriters, Rear Window serves as a shining example of how restricted perspective can amplify mystery and suspense. In this blog, we’ll explore the techniques used in Hitchcock’s Rear Window, breaking down its storytelling mechanics and extracting lessons to improve your writing craft.

The Setup: A Limited World

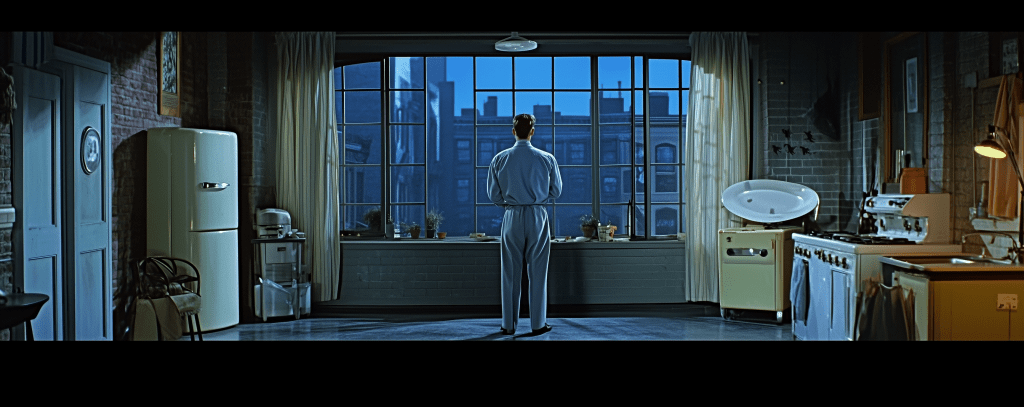

The premise of Rear Window is deceptively simple: L.B. “Jeff” Jefferies (James Stewart), a professional photographer, is confined to his New York apartment with a broken leg. Stuck in a wheelchair, his only form of entertainment becomes observing his neighbors through the window of his apartment. Soon, he begins to suspect that one of them, Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), has murdered his wife.

Hitchcock limits the world of the film almost entirely to Jeff’s perspective. The camera never ventures beyond what Jeff himself can see. This restricted point of view creates both opportunities and constraints:

- Opportunities: It allows the audience to share in Jeff’s growing paranoia and obsession. By withholding information, Hitchcock keeps viewers guessing.

- Constraints: The narrative must sustain itself within a single location and limited action.

This simple setup forces the story to rely on visual storytelling, character dynamics, and an escalating sense of unease. For screenwriters, it’s a masterclass in making a story feel vast within confined parameters.

Suspense Through Visual Storytelling

In Rear Window, Hitchcock proves that dialogue is not always necessary to advance the story or create tension. Much of the suspense comes from what Jeff sees—or thinks he sees—through his camera lens.

1. Creating Curiosity with Small Details

Suspense builds gradually in Rear Window. Instead of jumping straight to overt threats, Hitchcock plants seeds of doubt:

- Mrs. Thorwald’s sudden disappearance.

- Lars Thorwald’s peculiar late-night behavior, including carrying heavy suitcases and making repeated trips out of the apartment.

- The small but unsettling visual cue of Thorwald cleaning a large saw and knife.

Each detail, while seemingly insignificant on its own, combines to form a growing puzzle. The audience, restricted to Jeff’s viewpoint, becomes an active participant in piecing together the narrative. As screenwriters, this highlights the power of planting information visually rather than spelling it out in dialogue.

2. Playing with the Audience’s Perception

By adopting Jeff’s limited perspective, Hitchcock invites viewers to question what they’re seeing. Are Jeff’s suspicions grounded in reality, or is his boredom and isolation driving him to paranoid conclusions?

- At several points, characters like Jeff’s girlfriend Lisa (Grace Kelly) and nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter) express doubts, challenging Jeff’s narrative.

- The audience, like Jeff, is left searching for clues and second-guessing assumptions.

This creates a back-and-forth tension: is the threat real, or is Jeff projecting meaning onto innocent behaviors? Hitchcock masterfully uses ambiguity to keep us on edge.

Restricted Perspective: Immersion and Identification

One of Hitchcock’s most brilliant choices in Rear Window is making Jeff’s perspective synonymous with the audience’s perspective. By restricting the camera to Jeff’s vantage point, Hitchcock traps us in the same confined world, sharing Jeff’s sense of frustration and powerlessness.

1. Immersion Through Camera Techniques

The film never gives us omniscient information. Every shot mirrors Jeff’s field of vision:

- When Jeff uses binoculars or a telephoto lens, the audience sees through the same tools. This creates an intense, almost voyeuristic immersion.

- Conversely, when Jeff cannot see something (e.g., when curtains close or lights turn off), the audience is equally blind.

This technique increases suspense because the viewer can only observe clues in the same limited way as the protagonist.

2. Identification with the Protagonist

By aligning the audience with Jeff’s viewpoint, Hitchcock encourages identification. Jeff’s immobility becomes our immobility. We share his helplessness as events escalate:

- Jeff cannot investigate Thorwald himself because of his broken leg. This limitation builds tension as he must rely on Lisa and Stella to act on his behalf.

- Hitchcock amplifies our anxiety with brilliant timing. For example, when Lisa sneaks into Thorwald’s apartment, the suspense is heightened because we are stuck watching helplessly through Jeff’s—and by extension, the audience’s—point of view.

This alignment with Jeff deepens our emotional investment. We become complicit in his voyeurism, sharing both his fear and thrill.

Conflict and Escalation

Hitchcock’s use of limited perspective forces the conflict to escalate creatively. With Jeff physically confined and the story restricted to one location, the script focuses on inventive ways to raise stakes.

1. From Curiosity to Threat

The suspense starts small—Jeff’s innocent observations of neighbors—but escalates into a life-and-death situation:

- Jeff transitions from curiosity to suspicion as he collects circumstantial evidence against Thorwald.

- The stakes rise when Thorwald begins to suspect that someone is watching him, creating a cat-and-mouse dynamic.

This gradual escalation keeps viewers hooked, showing that a well-paced buildup can be just as thrilling as action-packed sequences.

2. The Role of Secondary Characters

Despite Jeff’s limited mobility, supporting characters like Lisa and Stella drive the action forward.

- Lisa becomes more involved as she moves from skeptic to believer, ultimately taking the dangerous step of entering Thorwald’s apartment.

- Stella provides comic relief but also grounds Jeff’s paranoia with her practical wisdom.

These characters serve as extensions of Jeff’s limited perspective, expanding the scope of the story without breaking its central conceit.

Themes: Voyeurism and the Ethics of Observation

Beneath the suspense, Rear Window explores deeper themes of voyeurism, privacy, and moral ambiguity:

- Jeff’s obsessive watching raises ethical questions: Is he justified in spying on his neighbors? At what point does curiosity cross a moral line?

- The film makes viewers complicit in this voyeurism. By aligning us with Jeff’s perspective, Hitchcock forces us to examine our own relationship with observation and entertainment.

For screenwriters, this highlights how genre storytelling can double as a commentary on societal issues. A suspense thriller can still raise thought-provoking questions while delivering an engaging plot.

Lessons for Screenwriters

Hitchcock’s Rear Window provides several takeaways for writers looking to craft suspenseful and immersive stories:

- Limit the Perspective: Restricting what the audience sees can heighten tension and immerse viewers in the protagonist’s experience. This technique works especially well for thrillers and mysteries.

- Build Suspense Through Details: Use visual storytelling to plant small clues that build over time, leading to a larger mystery. Trust the audience to pick up on these details.

- Escalate Conflict Creatively: When physical action is limited, focus on raising the stakes through character choices, timing, and pacing.

- Play with Ambiguity: Keep the audience guessing by presenting conflicting information and challenging their perceptions.

- Explore Larger Themes: Even within a genre story, consider deeper themes that resonate on an emotional or societal level.

Conclusion

Rear Window remains a timeless example of how limited perspective can create unparalleled suspense and emotional engagement. By restricting what the audience sees, Hitchcock pulls us into the story, making us both accomplices and participants in Jeff’s voyeuristic journey.

For screenwriters, the film serves as a masterclass in visual storytelling, pacing, and building tension. Whether you’re writing a contained thriller or a broader narrative, Rear Window demonstrates that limitations—far from being a creative barrier—can inspire some of the most compelling storytelling.

Next time you’re stuck in a story, ask yourself: What if the audience only knew what the protagonist knows? Sometimes, less really is more.

✍️ Whether you’re mastering the art of dialogue, structure, or character development, the power of AI can be a game-changer in your writing journey. My Free Ebook, ‘AI for Authors’ delves into how AI-powered prompts can provide a unique edge to your storytelling process. If you’re intrigued by the prospect of supercharging your fiction skills, download your free copy today and explore new horizons in creative writing.