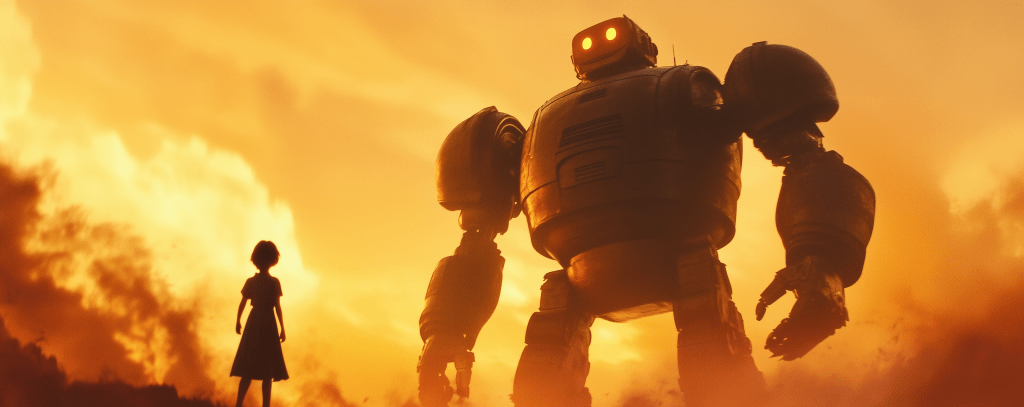

Animation often walks a delicate line between entertaining younger audiences and exploring deeper, often universal themes. Few films have achieved this balance as deftly as Brad Bird’s The Iron Giant (1999). Adapted from Ted Hughes’ novel The Iron Man, this animated feature tells the story of Hogarth Hughes, a young boy who befriends a towering robot from outer space. While its surface appeal lies in thrilling action and heartfelt friendship, the screenplay is a masterclass in weaving profound real-life themes—such as fear, identity, and the human capacity for both destruction and redemption—into an animated narrative.

In this article, we’ll explore the screenwriting brilliance behind The Iron Giant, analyzing its structure, character development, dialogue, and thematic depth. For screenwriters, it provides a blueprint for crafting family-friendly stories that resonate across generations.

The Power of a Simple, Universal Premise

At its heart, The Iron Giant is a “boy and his otherworldly friend” story, a familiar trope seen in classics like E.T. and The Jungle Book. This simplicity is one of its strengths. Screenwriter Tim McCanlies, working alongside Bird, keeps the premise straightforward while imbuing it with layers of emotional and thematic complexity.

The story takes place during the Cold War, a period of palpable tension and paranoia. By rooting the film in this historical moment, the screenplay immediately establishes a world of fear and suspicion. Hogarth’s small-town setting is relatable, but the looming presence of the government and militaristic attitudes make the stakes feel global.

For screenwriters, the lesson here is clear: a simple premise is not a limitation. When paired with rich subtext and context, it becomes a foundation for stories with immense emotional and intellectual depth.

Building Complex Characters in a Simplified World

One of the standout features of The Iron Giant is its character development, which makes every figure in the film, from Hogarth to the titular robot, feel multidimensional.

Hogarth Hughes: A Relatable Protagonist

Hogarth’s arc is the emotional core of the story. He’s a bright, lonely kid with a penchant for science fiction and a longing for connection. The script smartly establishes his curiosity and courage in the opening scenes—Hogarth is the type of child who not only dreams big but also acts on those dreams. This makes his relationship with the Giant believable and earned.

Through Hogarth, the audience learns the importance of empathy and critical thinking. The screenplay avoids the trap of making him a precocious, “perfect” kid; his temper and impulsiveness feel real. This relatability grounds the film’s more fantastical elements.

The Iron Giant: A Machine with a Soul

The Giant himself is one of animation’s most enduring creations, thanks to both Bird’s direction and the screenplay’s thoughtful handling of his character. The robot is a blank slate at first, learning morality and self-awareness through Hogarth’s guidance. This journey is rich with symbolism, mirroring human development and asking profound questions: Can we choose what we become, or are we doomed to follow our programming?

The Giant’s ultimate decision to reject his destructive origins—most powerfully encapsulated in his whispered affirmation, “I am not a gun”—is a testament to the screenwriter’s skill in merging character development with thematic resonance.

Supporting Cast: Aiding the Themes

The supporting characters are similarly nuanced. Dean McCoppin, the beatnik artist, serves as a counterbalance to the era’s conformity and fearmongering. His laid-back demeanor and philosophical outlook encourage Hogarth to think outside societal norms.

Conversely, Kent Mansley, the paranoid government agent, represents the dangers of blind fear and unchecked authority. He’s a caricature of Cold War hysteria, yet he’s written with enough depth to feel like a genuine threat rather than a cartoon villain.

The interplay between these characters deepens the story’s exploration of moral choices, making every interaction purposeful. For screenwriters, The Iron Giant serves as a reminder that secondary characters should not exist solely to fill space—they should actively contribute to the protagonist’s journey and the story’s themes.

Dialogue that Balances Humor and Gravitas

Animation, particularly family-oriented films, often relies on humor to keep younger audiences engaged. The Iron Giant uses humor effectively without ever undercutting its serious moments.

Take, for example, Hogarth’s early conversations with the Giant. Their exchanges are simple but layered, with Hogarth teaching the robot about Earth while the Giant’s childlike responses elicit both laughter and pathos. These scenes establish their bond while subtly introducing the film’s larger questions about identity and morality.

The screenplay also excels at using dialogue to highlight contrasts between characters. Kent Mansley’s exaggerated patriotism and condescension provide comedic relief, but his rhetoric also underscores the insidious nature of fear-driven ideology. Similarly, Dean’s laid-back, sardonic wit serves as a counterpoint to Mansley’s intensity, reinforcing the film’s central conflict between open-mindedness and fear.

For screenwriters, The Iron Giant demonstrates the importance of dialogue that serves multiple purposes. Every line should not only entertain but also reveal character, advance the plot, or reinforce the theme.

Themes Rooted in Real Life

The thematic depth of The Iron Giant is what elevates it from a good animated film to a timeless masterpiece. By weaving real-world concerns into its narrative, the screenplay ensures the story resonates with audiences of all ages.

The Fear of the Other

Set against the backdrop of the Cold War, the film explores humanity’s fear of the unknown. The Giant, despite his gentle nature, is immediately perceived as a threat by the authorities. This fear leads to catastrophic consequences, mirroring the real-world dangers of paranoia and xenophobia.

The Choice to Be Good

Central to the story is the idea that we are not defined by our origins. The Giant, designed as a weapon, grapples with his destructive programming but ultimately chooses to be a protector. This message—that individuals have the power to define their identity and actions—resonates deeply, particularly in a world often quick to label and judge.

The Cost of War

The film doesn’t shy away from depicting the destructive consequences of militarism. The climax, in which the Giant sacrifices himself to prevent a nuclear disaster, is a poignant reminder of the cost of fear-driven aggression. Yet, the hopeful ending reinforces the idea that peace and understanding are possible.

By addressing these themes within an accessible, engaging narrative, The Iron Giant achieves what many films—animated or otherwise—struggle to do: it entertains while provoking meaningful reflection.

A Well-Structured Story with Emotional Payoff

The screenplay of The Iron Giant adheres to classic three-act structure, ensuring a tight, emotionally satisfying narrative.

Act One: Setting the Stage

The opening scenes establish the world, tone, and stakes. We see Hogarth’s curiosity, the town’s paranoia, and the Giant’s mysterious arrival. The inciting incident—Hogarth’s discovery of the robot—occurs early, propelling the story forward.

Act Two: Building Relationships and Conflict

The second act focuses on Hogarth teaching the Giant about humanity while hiding him from the authorities. The stakes escalate as Mansley closes in, and the Giant begins to grapple with his destructive instincts.

Act Three: The Climax and Resolution

The third act delivers an emotional and action-packed payoff. The Giant’s ultimate sacrifice and the townspeople’s recognition of his humanity tie together the film’s thematic threads, leaving audiences moved and inspired.

For screenwriters, The Iron Giant is a case study in how to build tension, develop relationships, and deliver a cathartic conclusion—all while staying true to the story’s emotional core.

Conclusion: Lessons for Screenwriters

The Iron Giant remains a benchmark in animated storytelling, and its screenplay is a treasure trove of lessons for writers:

- Start with a universal premise: Simple setups allow for complex exploration.

- Ground characters in relatability: Even fantastical beings need human emotions and motivations.

- Use dialogue purposefully: Humor, exposition, and thematic resonance can coexist.

- Explore meaningful themes: Audiences of all ages appreciate stories that reflect real-life concerns.

Above all, The Iron Giant shows that animation is not a genre but a medium—a powerful vehicle for storytelling that can tackle the same profound questions as any live-action film. For screenwriters, it’s proof that heart, humanity, and imagination can elevate even the simplest of tales into enduring art.

✍️ Whether you’re mastering the art of dialogue, structure, or character development, the power of AI can be a game-changer in your writing journey. My Free Ebook, ‘AI for Authors’ delves into how AI-powered prompts can provide a unique edge to your storytelling process. If you’re intrigued by the prospect of supercharging your fiction skills, download your free copy today and explore new horizons in creative writing.